Countries Response for People With Disabilities During the COVID-19 Pandemic

- 1University of Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia

- 2Hannover Medical School, Hanover, Germany

Background and Objectives: During the Coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) pandemic, isolation and prevention measures to reduce COVID-19 contagions are essential for the care of all people; these measures should comply with the principles of inclusion and accessibility for people with disabilities (PWD), with all kinds of deficiencies and levels of dependency. Thereby, the aim of this article is to present the measures adopted for PWD or people with rehabilitation needs, for containment, mitigation, or suppression of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in different countries of all continents and of all income levels.

Methods: A narrative approach was used in this article. First, a broad search was carried out in the 193 member states of the UN, and then 98 countries that issued any document, report, or information related to disability and COVID-19 were selected. Finally, 32 countries were included in this article because they presented official information. We considered official sources, the information available in the government, or on the health ministry page of the country. In this way, the countries that presented information which did not correspond to an official source were excluded. The search was conducted in August 2020 and updated in March 2021.

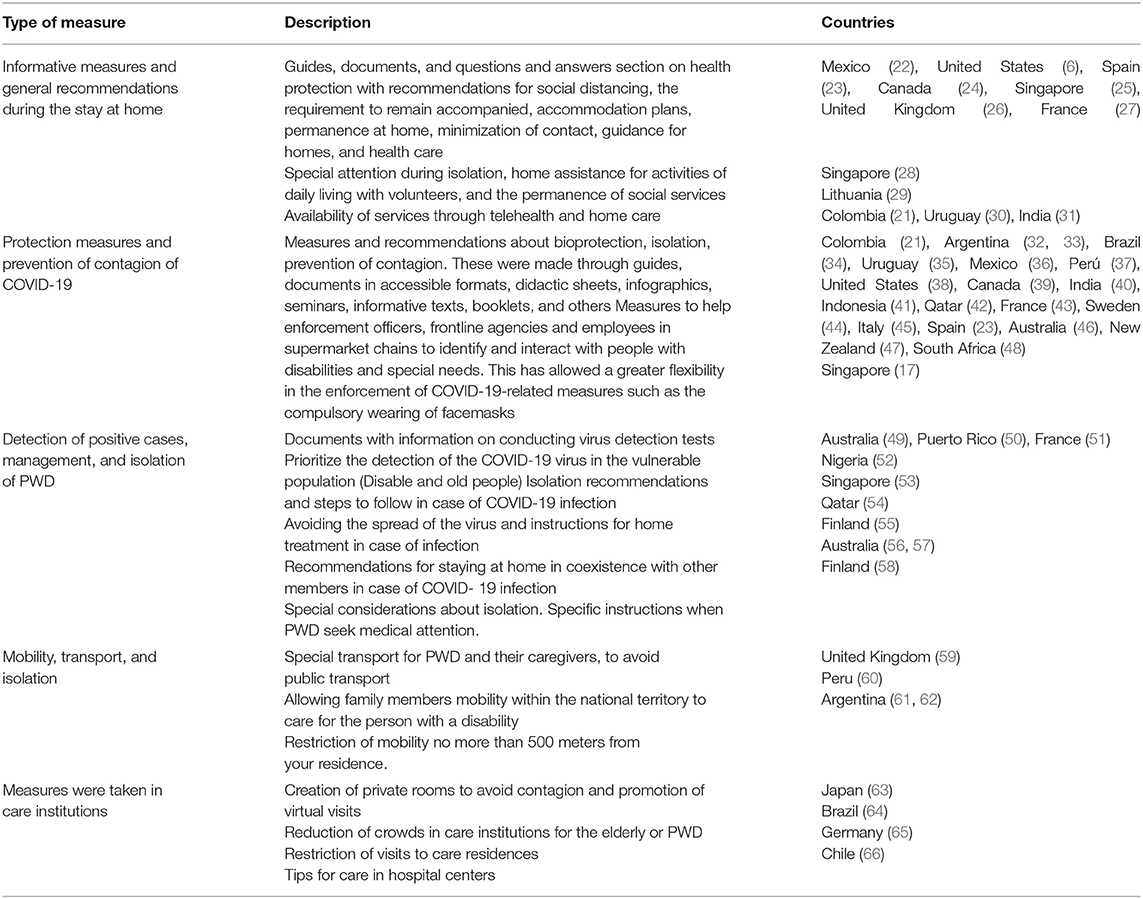

Results: First, the non-pharmacological general interventions for PWD included informative measures and general recommendations during the stay at home, isolation, and biosecurity measures, contagion prevention, detection of positive cases, mobilization measures, and measures implemented in institutions or residences of PWD. Second, we identified the economic and social benefits provided to PWD during the pandemic. Finally, we identified the measures taken by countries according to the type of impairment (visual, hearing, physical, mental, and cardiopulmonary impairment) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion: In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, only 50% of countries from the five world regions created and implemented specific measures for PWD to containment, mitigation, or suppression of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. There is very little specific information available about the measures to continue with the care of people with rehabilitation needs and the long-term follow-up of PWD, and for the prevention and response to violence, especially for women with disabilities.

Introduction

The Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic began in the city of Wuhan (China) at the end of 2019 and it was declared, according to the WHO (1), as such in March 2020. With 233,136,147 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 4,771,408 deaths worldwide (as of September 30, 2021) (2). It drastically changed the priorities of the entire planet, and it made those countries from the five world regions create and adopt isolation and prevention measures to reduce infections in a short time. Furthermore, these measures, which were essential for the care of all people, had to comply with the principles of inclusion and accessibility for all vulnerable population groups.

More than a billion people in the world experience disability nowadays. The current demographic and health shifts are contributing to a rapid increase in the number of people experiencing disability or decline in functioning for substantially larger periods of their lives (3). This number is increasing globally, in part due to aging populations and due to an increase in chronic health conditions (4). Thereby, these trends create increasing demands for health and rehabilitation services, which are very far from being met, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (5).

People with disabilities (PWD) represent a vulnerable population; in this way Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and WHO stated that some PWD may be more likely to become infected with the SARS- CoV-2 virus, or may develop a serious illness due to the underlying medical conditions, congregational living environments, systemic social inequities, and some barriers they might face in accessing healthcare during the pandemic (6–8). Thereby, rehabilitation must be an integral part of COVID-19 management, and it must be kept a health priority during the COVID-19 pandemic, and given adequate financial resources (9). Therefore, each country needs to develop specific strategies for PWD to protect its rights.

It is expected that COVID-19 affects this vulnerable population. Too often, PWD is left behind in emergencies, and this is a risk in the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic (7). Pandemics, such as COVID-19, place everyone at risk, but certain risks are differentially more severe for groups already vulnerable by the preexisting forms of social injustice and discrimination (10). For this reason, any response to the pandemic must be bound with the legal standards, principles of distributive justice, societal norms of protecting vulnerable populations, and core commitments of public health, to ensure that established inequities are not exacerbated (11).

In some countries where health services have been accessible and affordable, governments find it increasingly difficult to respond to the growing health needs of populations and the rising costs of health services (12). During the COVID-19 pandemic, rehabilitation services are facing additional challenges. These services have been defined in many settings as “non-essential,” and many of them have been canceled or limited, for instance, by limiting the care to outpatient settings (9, 13, 14). Furthermore, the huge impact of the COVID-19 pandemic left some patients, families, and caregivers alone with their needs. Associations made great efforts to assist their members by offering information, advice, and individual support (15).

In this way, rehabilitation services must keep continuing during the pandemic; it is an essential component of high-value care to optimize physical and cognitive functioning to reduce disability. In this way, the interruption of these services may affect the well-being and quality of life of PWD and impose more burdens on a population that is already vulnerable (9, 16). Some medical conditions, such as stroke, spinal cord injury, and cardiopulmonary conditions can be aggravated by a lack of access to rehabilitation services (9).

One study described the timely innovative proposals of scientific associations and rehabilitation professionals of different countries, focusing on delivering rehabilitation services, protection and prevention measures, physical distancing, isolation, hand washing, and disinfection measures in the context of the COVID- 19 pandemic. In this way, measures to prevent and protect against transmission of COVID-19 are necessary for all patients in rehabilitation care around the world (17).

Bettger (16) published a commentary to describe the adjustments to the continuum of rehabilitation services across 12 low-income, middle-income, and high-income countries in the context of national COVID-19 preparedness responses and to provide recommendations for decision-makers on the provision and payment of these essential services (18). Another study presented information about 38 countries that showed a huge impact on PWD due to a reduction in all rehabilitation activities in Europe in all the settings, such as acute, postacute, and outpatients (14).

This information allows for knowing some of the adaptations and reorganization of the rehabilitation services carried out in different countries to the health emergency by COVID-19, which had an impact on PWD or with rehabilitation needs (17, 18). Until now, it is known about the response to PWDs that some supranational organizations, rehabilitation associations, and some countries have had during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, a recompilation of the measures of different countries of the five regions of the world has not been made up till now.

The main aim of this study was to describe the measures adopted by different countries around the world and of all income levels to guarantee universal coverage, access to information, and actions for prevention and mitigation of direct and indirect consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, on PWD and with rehabilitation needs.

Methods

We used a narrative approach (19) to identify countries' responses to PWD and rehabilitation needs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Research Question

Which were the responses and measures adopted by different countries for PWD and with rehabilitation needs, for containment, mitigation, or suppression of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic?

Search Strategy

Selection, Extraction, and Categorization of Information

A narrative approach was used to identify the measures adopted by different countries for PWD or with rehabilitation needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. First, a broad search was carried out in the 193 member states that belong to the UN (20). Then 98 countries that issued any document, report, or document related to disability and COVID-19 were selected.

In this way, the countries that presented information that did not correspond to an official source were excluded. We considered the official sources, the information available in the governments, or the health ministry pages of the country. Thus, we excluded 66 countries that presented information that did not correspond to an official source. We considered the following official sources: (1) The information is available on the government page of the country. (2) The information is available on the ministry page of the country. We excluded other sources of information, such as NGOs, foundations, private organizations, or independent organizations because this was not the focus of this review. The search was conducted in August 2020 and updated in March 2021.

Eight researchers (MAS, KMC, AMP, JCV, LM, RD, MG, and VO) conducted the data extraction using a predefined form to record the following information: (1) date of the declaration of emergency; (2) specific measures for PWD related to social distancing, biosecurity measures, travel restrictions, detection and tracking of cases, isolation of cases of PWD, economic benefits, and others related to the guarantee of rights; and, (3) specific measures according to the type of disability: hearing disability, visual disability, physical disability, cardiopulmonary limitation, intellectual disability, autism, and dementia.

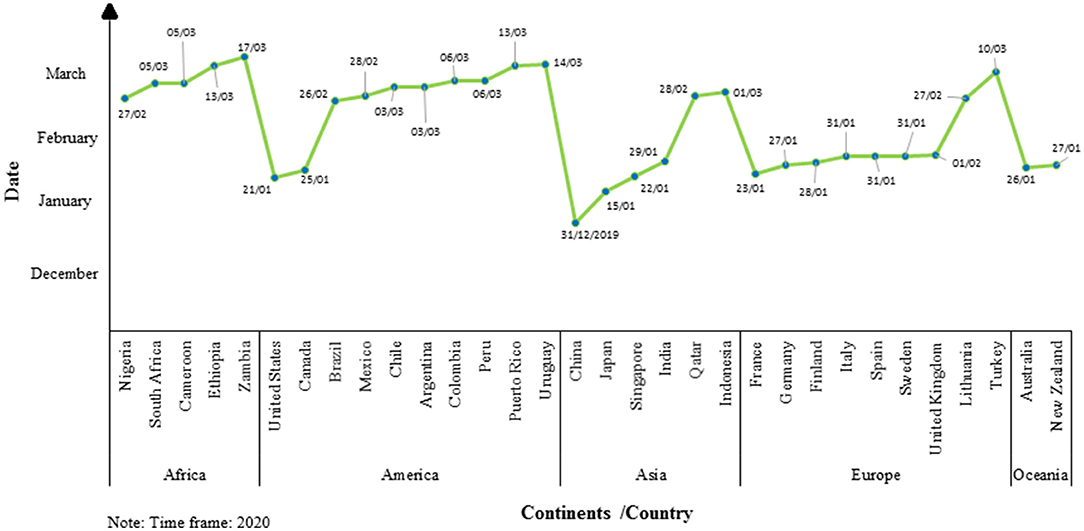

Finally, four researchers with expertise in rehabilitation screened the search results and selected 32 countries from five world regions: Africa (5 countries), America (10 countries), Asia (6 countries), Europe (9 countries), and Oceania (2 countries). Hence, 32 countries were included in this article because they presented official information issued by the government or the health ministry's official pages (refer to Figure 1).

Figure 1. Line graph of the date of declaration of health emergency by COVID-19 according to the countries and continents in the world.

We categorized the information in non-pharmacological interventions for general PWD and interventions according to specific types of disabilities. First, we included the following interventions: informative measures and general recommendations during the lockdown, protection measures and prevention of COVID-19 contagion, detection of positive cases, management, and isolation of PWD; mobility, transport, and isolation; and measures taken within care institutions. Then, we categorized the interventions according to the following types of disability: visual impairments, hearing impairments, physical disability, cardiopulmonary limitation, and mental function that included autism, dementia, and intellectual disability.

Results

The findings reflect that some governments have made an effort for reducing the transmission of the disease in this vulnerable population because they have recognized the importance of providing access to health services and the need to adopt special and different measures for the prevention of contagion in PWD (21) (refer to Table 1).

Measures According to the Type of Deficiency During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Some countries made a declaration that PWD could have a greater vulnerability in this pandemic because they are constantly faced with physical barriers in the application of hygiene measures or social distancing. Besides, they require support from other people to carry out their daily activities (16).

In this synthesis, we considered the following impairment conditions: visual, hearing, physical impairments, cardiopulmonary limitations, and alterations in mental function (Tables 2–6).

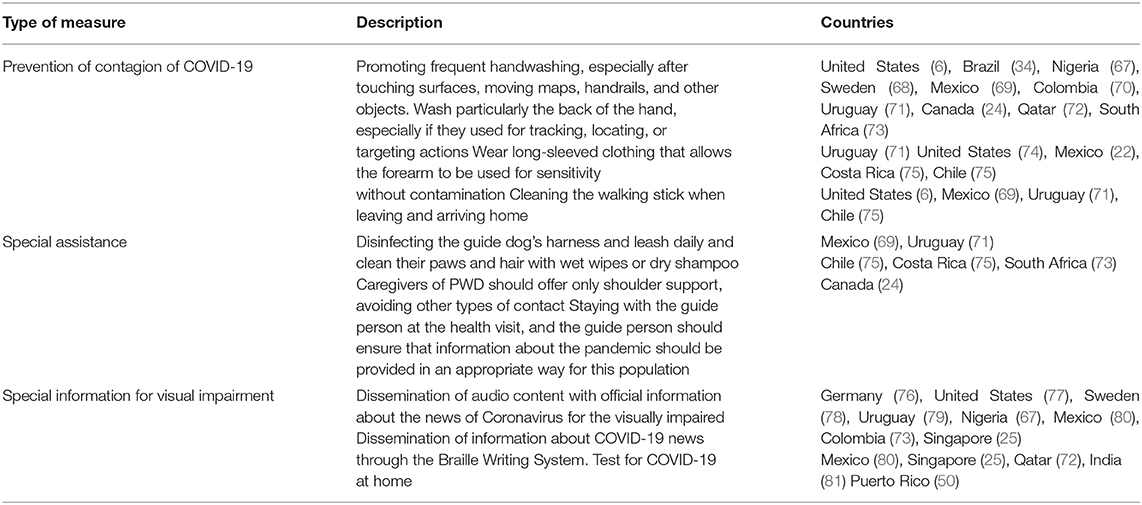

People With Visual Impairment During the COVID-19 Pandemic

People with visual impairments may have a higher risk of contagion by SARS-CoV-2 because daily they need to be in contact with objects, surfaces, or assistive devices to recognize the environment and to move in the space. For this reason, the countries around the world focused on recommendations based on frequent handwashing, cleaning of assistive devices, such as sticks, guide dogs, and other recommendations mentioned in Table 2.

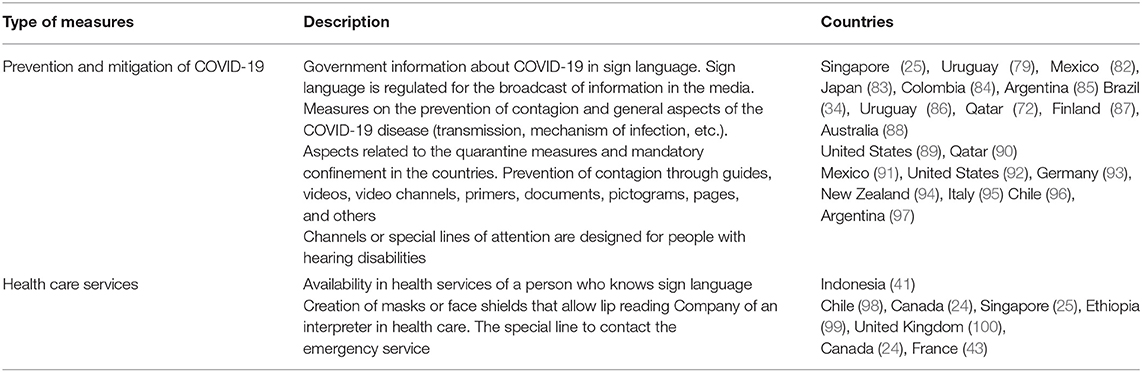

People With Hearing Impairment in COVID-19 Times

Around all continents, the need to implement sign language to obtain better and clearer access to all information about COVID-19 has been recognized. This action would improve the rights of people with hearing impairment. The government states that not only translation is important, but it needs actions to prevent and mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in this population, such as the following measures shown in Table 3.

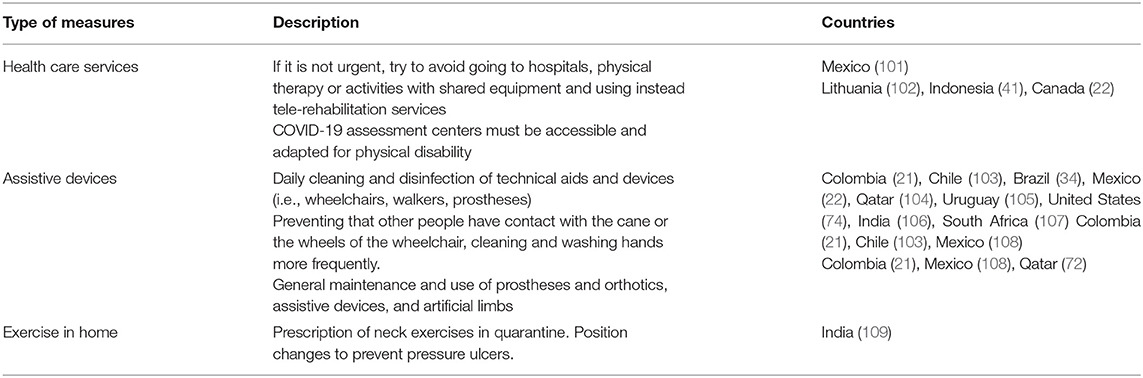

People With Physical Impairment in COVID-19 Times

Most of the countries have a general concern regarding the people with physical disabilities, that is the cleaning of assistive devices and surface contact areas because this population usually needs help from another person and close contact with people or their own devices (refer to Table 4).

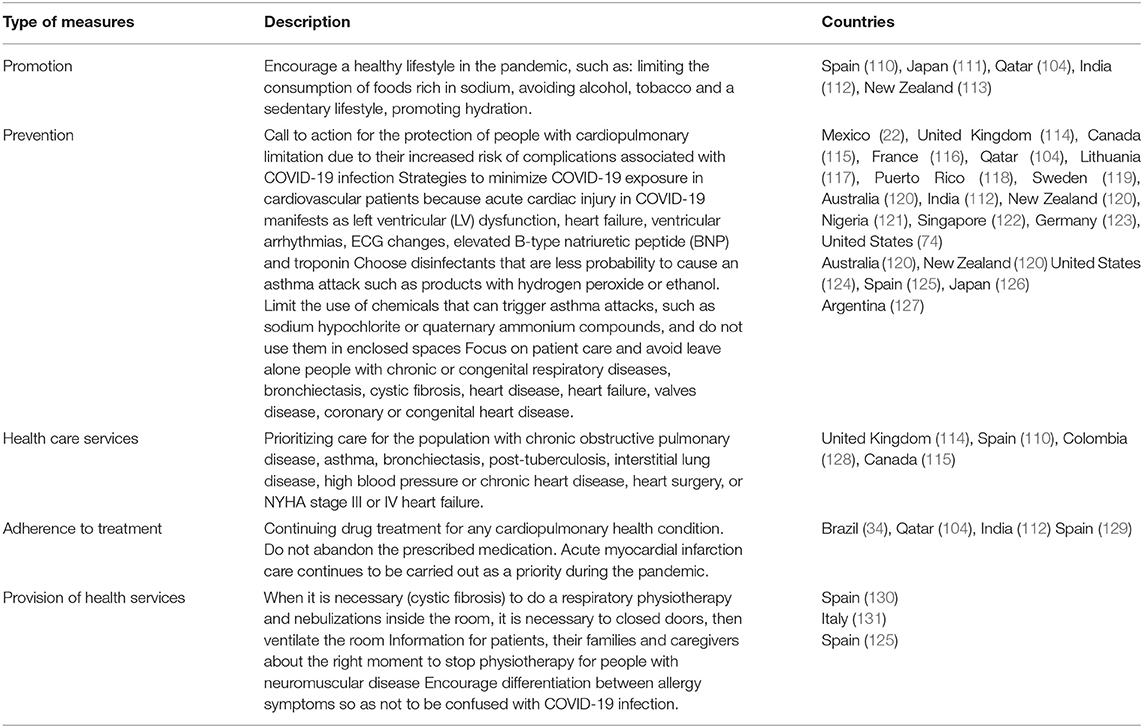

People With Impaired Cardiopulmonary Function in COVID-19 Times

Countries focus their attention on preventing contagion by COVID-19 in people with any impaired cardiopulmonary function because they have a higher risk to develop secondary complications due to Coronavirus. In this way, most measures seek to prioritize the special care that this population group should have when they have a virus infection (refer to Table 5).

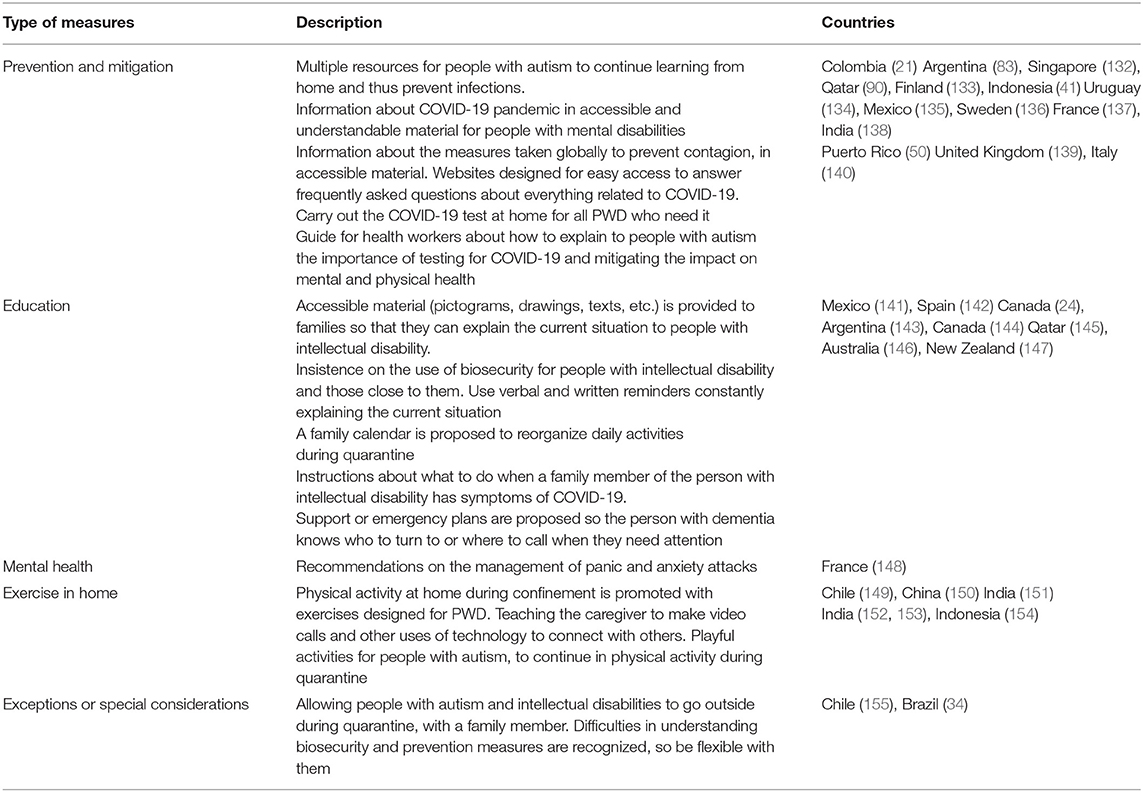

People With Any Alteration in the Mental Function During COVID-19 Times

Some countries issued information focused on recommendations to orient people with autism, intellectual disabilities, or dementia. Governments issued information in easy-to-read material with information focused on prevention measures to avoid the spread of the virus. Furthermore, countries issued recommendations and advice about the care of mental health in this population during the pandemic (refer to Table 6).

Table 6. Measures for people with any alteration in the mental function during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Economic and Social Benefits Provided to PWD During the Pandemic

Some American countries, such as Colombia, created programs to identify the PWD who had support needs to ensure their levels of quality of life and food security during the COVID-19 state of emergency (156). Chile made economic donations to PWD (157). Argentina provided economic assistance, such as residences for PWD with the aim of covering expenses for the acquisition of supplies and protection elements directly related to avoiding the COVID-19. Also, they provided financial assistance to the PWD for the acquisition of prophylaxis, prevention, diapers, medicines, and food linked to specific deficiencies or pathologies (158).

Brazil invested in the Social Assistance System with the aim of maintaining programs, projects, and services in the vulnerable areas of the country, mainly for the care of PWD and the elderly (159). The United States earmarked some grants to support PWD and to provide food for the elderly (160).

The European countries, such as France made exceptional provisions to avoid any violation of the rights of the holders of the allowance for PWD, to deal with the social and economic consequences of the COVID-19 epidemic (161). Italy provided bonuses to families to cover the costs of caring for children with disabilities (162). The United Kingdom created some support strategies for PWD, for example, a program of volunteers for the purchase of obtaining essential products and claiming the medicines of PWD. Besides, the PWD received a weekly box of basic supplies, and they were a priority population for deliveries in supermarkets (163).

In Asian countries, such as Japan, there were guidelines for financial support for children with disabilities, due to the temporary closure of special support schools (164). The government of India has a microcredit scheme for PWD to educate or train them in different areas, for their job performance (165); these subsidies were also implemented by other countries, such as Lithuania (102).

In some countries of Oceania, such as Australia, there was a payment to PWD to help them keep their jobs (166). New Zealand indicated what to do if PWD had financial support needs and they created a section with information according to the type of support required, for example, accommodation costs, electricity, gas, water or heating bills, food, school or office costs, and other costs and a guide to help manage money (167).

In Africa, the country of Zambia carried out an inclusive, multi-partner socio-economic impact study on the effects of the COVID-19 outbreak to ensure that no one was left behind by targeting the most vulnerable group, such as PWD and the marginalized groups (168).

Discussion

In this narrative review, we described the non-pharmacological interventions for PWD that included informative measures and general recommendations during the quarantine period, isolation, and biosecurity measures, contagion prevention, detection of positive cases, mobilization measures, measures implemented in institutions or residences of PWD, the main economic and social benefits provided to PWD, and the measures taken by countries according to the type of impairment (visual, hearing, physical, mental, and cardiopulmonary) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The WHO called for an action to strengthen the rehabilitation planning and implementation, including sanitary emergency preparedness and response to the current COVID-19 pandemic (8, 169). In this way, the results obtained in this synthesis showed that there has been a response to the COVID- 19 pandemic by 50% of the countries belonging to the United Nations with the aim to protect the health and well-being of PWD, which allows for increasing the visibility of PWD in the society.

The disability considerations of WHO during the COVID-19 outbreak included the following: the provision of accessible information; provision of health services via telemedicine and through community-based networks, ensuring equitable healthcare access; guidelines prohibiting blanket decisions on medical rationing, solely on the grounds of disability, employment, and financial protection delivered through disability-related welfare provision; the development of support frameworks for people who need to shield from COVID-19 but who are outside of the social welfare or social care context (e.g., reasonable adjustments in employment working arrangements); education interventions and reasonable accommodations through online special education classes, accessible education activities, and distribution of educational materials; social care services, including psychosocial support, personal assistance, and support for independent living; prevention from and response to violence, in the forms of accessible hotlines for gender-based violence, especially for disabled women, and emergency services and shelters prepared to meet the needs of the disabled people; measures addressing the intersectional disadvantage the disabled people face, including the early release of disabled prisoners, and the provision of accessible health services for homeless people; and the inclusion of disabled people in the recovery phase, ensuring that structural changes are implemented, making the societies more inclusive (8).

Therefore, it is evident that there has been a real concern for the protection of the rights of PWD by supranational organizations which called on governments to guarantee the protection and promotion of the rights of PWD, as evidenced in our recent synthesis about the rights of PWD during the COVID-19 pandemic (18).

Although there have been explicit statements about the prevention and mitigation measures from several countries, others did not do it, as many countries from Africa, Asia, and America especially, central America. Fewer were the declarations to continue with the care of people with rehabilitation needs and the long-term follow-up of PWD. These kinds of responses were timely and more creative on the part of a professional's associations (17). Only 35% of the countries had considerations about employment and financial protection of PWD and accessible education. There were few declarations about the prevention and response to violence, especially for disabled women.

Most of the countries involved in this synthesis had an inclusive response to the pandemic with the creation of measures for PWD but not all countries developed specific measures for each type of impairment. We also note that some countries developed guidelines about the recommendations to be taken for a specific type of disability, while other countries only issued a little information about it; also, some other countries only adapted the recommendations that other countries issued.

The North American countries had a broad focus on the population living in the residential centers or home cares. Some other countries in Europe, such as the United Kingdom and Spain, had a real concern for people with impaired cardiopulmonary function. Most of the recommendations issued by the countries for people with a physical impairment only focused on the cleaning of assistive devices or surface contact areas; however, the recommendations in this population could be covered in a broader way.

However, our findings are consistent with the WHO report that states that PWD may have a greater risk of acquiring COVID-19 because they daily deal with barriers to implementing basic hygiene measures, difficulty in carrying out the social distancing, the need to touch contact surfaces, assistive devices, or some objects to obtain information from the environment, or for the physical support. Besides, some others are institutionalized and others face barriers to the access of the public health information (8).

As Bettger (16) described, the national agencies did not issue specific guidance for the provision of rehabilitation care. According to our synthesis, some countries had a poor response, such as the countries of Africa, in which the information content was less than the other countries of America or Europe; we really do not know if this situation is due to a lack of response or if the measures have not been documented in the official pages. Also, these situations could be explained due to the short time for a COVID-19 response and the quick progress of the current pandemic (16).

Our results are consistent and support Armitage's approach that COVID-19 mitigation strategies must include PWD to ensure that they maintain respect for “Dignity, human rights, and fundamental freedoms, and avoid widening existing disparities” (7). This requires accelerating efforts to include these groups in preparedness and response planning, and requires diligence, creativity, and innovative thinking, to preserve our commitment to the Universal Health Coverage, and ensure that people living with disabilities are not forgotten (7).

Moreover, we share the approach of Ceravolo et al. (170) which stated that the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has challenged the provision of healthcare worldwide, highlighting the main flaws of some health systems concerning their capacity to cope with the needs of frail subjects.

Pandemics, such as COVID-19, place everyone at risk, but certain risks are differentially more severe for groups already vulnerable by the preexisting forms of social injustice and discrimination (10). For this reason, responses to the pandemic must be bound by legal standards, principles of distributive justice, and societal norms of protecting vulnerable populations, core commitments of public health, and to ensure that inequities are not exacerbated and should provide a pathway for improvements to ensure equitable access and treatment in the future (11).

Limitations

Even though an exhaustive search was made in the national pages of each country, relevant information, issued by different countries, such as reports, guides could have been disregarded due to the language of the information, or perhaps there was no easy way to access this information. The consensus process of recommendations is heterogeneous and, in some cases, not clear. Lack of evidence is inherent because no studies on long-term outcomes were available. Data about the care of PWD in low- and middle-income countries is lacking. There is little information about the measures to continue with the care of people with rehabilitation needs and the long-term follow-up of PWD. Besides, the information is scarce about the consequences of COVID-19 in PWD, and we do not know the effectiveness of the implementation of these prevention measures in disabled people or with rehabilitation needs.

Implications of the Review

We suggest that appropriate actions and prevention strategies for PWD should be implemented to reduce the contagion of COVID-19, such as vaccination prioritization, access in public places to wash hands when they are away from home, and provision of accessible information for this population through all media.

It is necessary to strengthen and provide health services through telemedicine, telerehabilitation, and home-based rehabilitation, ensuring equitable access to medical care. Besides, we suggest that PWD who need educational interventions and reasonable accommodations for learning can use other methods for their learning, such as online special education classes or accessible educational activities. Also, we consider it important to strengthen social care services for PWD in times of confinement and social distancing.

In those countries where specific guidance for the provision of rehabilitation for PWD was not prioritized, we recommend that national rehabilitation associations and providers make statements to ensure access to rehabilitation services.

Therefore, we call for action from all authorities and other stakeholders to continue and strengthen the creation of measures that manage to address the needs of PWD and to reduce the barriers they experience in the current pandemic. In this contingency, it has not been enough to maintain the health care conditions for PWD. The need to work on strengthening communication and innovation in health care, the integration of countries and human groups to build the way of living in a new world, called the ‘New Normal’ is evident.

Conclusion

In summary, our findings suggest that most countries around the world have adopted appropriate actions, creating and designing measures and strategies for PWD in response to the health emergency due to COVID-19. The response of different countries to the pandemic showed the need to implement actions for the prevention of contagion of PWD, their families, caregivers, and health professionals who provide rehabilitation services.

However, there is very little specific information available about the measures to continue with the care of people with rehabilitation needs and the long-term follow-up of PWD, and for the prevention and response to violence, especially for women with disabilities. Finally, it is important to highlight that PWD is still a vulnerable population because they are constantly facing barriers that hinder the implementation of prevention and protection measures in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Author Contributions

LL: definition of the research question and the objectives of the study, elaboration of the methodology for the research, selection of studies, data extraction, synthesis, elaboration of results, and writing the final article. MS: information selection, information research in different organizations, data extraction, information analysis, elaboration of the results, and writing the final article. JV: design and organization of templates for data extraction, content data extraction, and data organization and grouping. MG: analysis and preparation of results and annexes and writing the final article. AP: definition of the research question and the objectives of the study, elaboration of the methodology for the search, selection of studies, and data extraction. VO: synthesis, elaboration of results, selection, extraction, analysis of data from different associations, and writing the final article. LM: selection of studies, data extraction, and synthesis of results. KC: selection of information, information search in different organizations, data extraction, and information analysis. RD: selection, extraction, analysis of data from different associations, and writing the final article. CG: synthesis and elaboration of results and writing and reviewing the final article. DP: data extraction, synthesis and preparation of results, and writing the final article. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. WHO. Director-General's Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19. World Health Organization (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s- opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19 (accessed March 2, 2021).

2. Bellocchio L, Bordea IR, Ballini A, Lorusso F, Hazballa D, Isacco CG, et al. Environmental issues and neurological manifestations associated with COVID-19 pandemic: ¿new aspects of the disease? Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:E8049. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17218049

3. Cieza A, Causey K, Kamenov K, Hanson SW, Chatterji S, Vos T. Global estimates of the need for rehabilitation based on the Global Burden of Disease study 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. (2021) 19:1–12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32340-0

4. WHO. Disability and Health. World Health Organization (2020). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and- health (accessed March 2, 2021).

5. Mlenzana NB, Frantz JM, Rhoda AJ, Eide AH. Barriers to and facilitators of rehabilitation services for people with physical disabilities: a systematic review. Afr J Disabil. (2013) 2:1–6. doi: 10.4102/ajod.v2i1.22

6. Centers for Disease Control Prevention. (2021). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/humandevelopment/covid-19/people-with-disabilities.html (accessed March 07, 2021).

7. Armitage R, Nellums LB. The COVID-19 response must be disability inclusive. Lancet Public Health. (2020) 5:e257. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30076-1

8. World Health Organization. Disability Considerations During the COVID-19 Outbreak. WHO/2019-nCoV/Disability/ (2020). Available online at: bit.ly/Cov19disability (accessed Mar 2, 2021).

9. Gutenbrunner C, Stokes EK, Dreinhöfer K, Monsbakken J, Clarke S, Côté P, et al. Why rehabilitation must have priority during and after the COVID-19-pandemic: a position statement of the global rehabilitation alliance. J Rehabil Med. (2020) 52:1–4. doi: 10.2340/16501977-2713

10. Scully JL. Disability, disablism, and COVID-19 pandemic triage. J Bioeth Inq. (2020) 17:601–5. doi: 10.1007/s11673-020-10005-y

11. Sabatello M, Burke TB, McDonald KE, Appelbaum PS. Disability, ethics, and health care in the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Public Health. (2020) 110:1523–27. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305837

12. WHO. Universal Health Coverage (UHC). World Health Organization (2019). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact- sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-(uhc) (accessed Mar 3, 2021).

13. Negrini S, Kiekens C, Bernetti A, Capecci M, Ceravolo MG, Lavezzi S, et al. Telemedicine from research to practice during the pandemic. Instant paper from the field” on rehabilitation answers to the COVID-19 emergency. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. (2020) 56:327–30. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.20.06331-5

14. Negrini S, Grabljevec K, Boldrini P, Kiekens C, Moslavac S, Zampolini M, et al. Up to 2.2 million people experiencing disability suffer collateral damage each day of COVID-19 lockdown in Europe. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. (2020) 56:361–5. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.20.06361-3

15. Boldrini P, Garcea M, Brichetto G, Reale N, Tonolo S, Falabella V, et al. Living with a disability during the pandemic. “Instant paper from the field” on rehabilitation answers to the COVID-19 emergency. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. (2020) 56:331–4. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.20.06373-X

16. Bettger JP, Thoumi A, Marquevich V, De Groote W, Rizzo Battistella L, Imamura M, et al. COVID-19: maintaining essential rehabilitation services across the care continuum. BMJ Global Health. (2020) 5:1–7. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002670

17. Lugo-Agudelo LH, Sarmiento KM, Brunal MA, Correa JV, Borrero AM, Franco LF, et al. Adaptations for rehabilitation services during the COVID-19 pandemic proposed by scientific organizations and rehabilitation professionals. J Rehabil Med. (2021) 53:3–10. doi: 10.2340/16501977-2865

18. Lugo-Agudelo LH, Spir Brunal MA, Velásquez Correa JC et al. Rights of people with disabilities in the Covid-19 pandemic. Rapid review. Rev Col Med Fis Rehab. (2020). doi: 10.28957/rcmfr.v30spa8

19. Baethge C, Goldbeck-Wood S, Mertens S. SANRA - a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res Integr Peer Rev. (2019) 4:2–7. doi: 10.1186/s41073-019-0064-8

20. United States. Member States. Available online at: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/member-states (accessed March 2, 2021).

21. Social Promotion Office. Guidelines for the Prevention of Covid-19 Contagion Health Care for People With Disabilities, Their Families, Caregivers, Actors in the Health Sector. Colombia: Ministry of Health Social Protection (2020). Available online at: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/DE/PS/asif13-personas-con-discapacidad.covid-19.pdf (accessed March 7, 2021).

22. Government of Mexico. Practical and Accessible Recommendations to Take Care of Your Health and Your Rights in Times of Coronavirus. Mexico: Me too (2020). Available online at: https://coronavirus.gob.mx/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Guia-de-lectura-facil-yotambien-v2.pdf (accessed March 7, 2021).

23. Government of Spain. Frequently Asked Questions About the Social Measures Against the CORONAVIRUS COVID-19. Spain: Ponferrada Town Hall (2020). Available online at: https://www.ponferrada.org/es/ponferrada-hoy/preguntas-frecuentes-medidas-sociales-coronavirus-covid-19 (accessed March 7, 2021).

24. Government of Canada. COVID-19 and People With Disabilities in Canada. Canada: Goverment of Canada (2021). Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/guidance-documents/people-with-disabilities.html#a2 (accessed March 7, 2021).

25. Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Singapore's Reply to the Joint Communication From Special Procedures Mandate Holders on the Lack of Accessible Information on the COVID-19 Pandemic and Related Response for Persons With Disabilities, in Particular for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Persons. Singapore: Ministry of Foreign Affairs; (2020). Available online at: https://www.mfa.gov.sg/Overseas-Mission/Geneva/Mission-Updates/2020/07/Singapore-Reply-to-the-JC-for-SPMH-Covid-19-27-July-2020 (accessed March 7, 2021).

26. Department of Health & Social Care. Guidance on Shielding and Protecting People Who Are Clinically Extremely Vulnerable From COVID-19. Public Health England (2021). Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/guidance-on-shielding-and-protecting-extremely-vulnerable-persons-from-covid-19/guidance-on-shielding-and-protecting-extremely-vulnerable-persons-from-covid-19 (accessed March 7, 2021).

27. State Secretariat in charge of people with disabilities. Covid-19: Frequently Asked Questions. France: State Secretariat in charge of people with disabilities (2021). Available online at: https://handicap.gouv.fr/grands-dossiers/coronavirus/article/covid-19-foire-aux-questions (accessed March 2, 2021).

28. Government of Singapore. Safe Re-opening: How Singapore Will Resume Activities After the Circuit Breaker. Singapore: Government of Singapore (2020). Available online at: https://www.gov.sg/article/safe-re-opening-how-singapore-will-resume-activities-after-the-circuit-breaker (accessed March 7, 2021).

29. Department of Disability Affairs under the Ministry of Social Security Labor. On the Organization of Social Services From 18 May 2020. Lithuania: Department of Disability Affairs (2020). Available online at: http://www.ndt.lt/del-socialiniu-paslaugu-organizavimo-nuo-2020-m-geguzes-18-d/ (accessed March 7, 2021)

30. Government of Uruguay. COVID-19 and Attention to Disability. Uruguay: National Emergency System (2020). Available online at: https://www.gub.uy/sistema-nacional-emergencias/comunicacion/publicaciones/covid-19-atencion-discapacidad (accessed March 7, 2021).

31. Press Information Bureau Government Government of India. DoPT Memorandum. Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances & Pensions (2020). Available online at: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetail.aspx?PRID=1608923 (accessed March 7, 2021)

32. Government of Argentina. Economic Assistance Program for Homes and Residences for People With Disabilities in the Framework of the COVID-19 Emergency. Government of Argentina; (2020). Available online at: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/andis/programa-de-asistencia-economica-hogares-y-residencias-para-personas-con-discapacidad-en-el-marco-de (accessed March 14, 2021).

33. Argentine Ministry of Health. COVID-19 Recommendations of Assistance and Emotional Support for People With Disabilities. Argentine Ministry of Health (2020). Available online at: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/covid-19-recomendaciones-asistencias-personas-discapacidad.pdf (accessed March 7, 2021).

34. National Secretariat for the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. People With Disabilities and Rare Diseases and COVID-19. Beloved Country Brazil Federal Government (2020). Available online at: https://sway.office.com/tDuFxzFRhn1s8GGi?ref=Link (accessed March 7, 2021).

35. UNPRPD. Coronavirus Recommendations. Alliance to Promote the Services of People With Disabilities. (2020). Available online at: https://inclusionydiscapacidad.uy/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/ONU_Recomendaciones_Coronavirus_Generales_v3.pdf (accessed March 7, 2021).

36. Government of Mexico. CONADIS COVID19 Infographics in Text Version for Automated Readers. Government of Mexico; (2020). Available online at: https://www.gob.mx/conadis/documentos/infografias-conadis-en-version-texto-para-lectores-automatizados (accessed March 7, 2021).

37. Government of Peru. Government Establishes Prevention and Protection Actions for People With Disabilities During the State of Emergency Due to Covid-19. Government of Peru; (2020). Available online at: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/mimp/noticias/127647-gobierno-establece-acciones-de-prevencion-y-proteccion-para-las-personas-con-discapacidad-durante-el-estado-de-emergencia-por-el-covid-19 (accessed March 7, 2021).

38. AUCD. Advice From People Who Have a Disability on Dealing with COVID-19. Association of University Centers on Disabilities (2020). Available online at: https://www.aucd.org/template/event.cfm?event_id=8646 (accessed March 7, 2021).

39. Government of Canada. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Prevention and Risks. Government of Canada (2021). Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/prevention-risks.htm (accessed March 7, 2021).

40. Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment. Home Whats New. Department of empowerment of Persons with Disabilities (Divyangjan) (2020). Available online at: http://disabilityaffairs.gov.in/content/page/whats-new.php (accessed March 7, 2021).

41. Ministry of Social Affairs. Health Protection and Psychosocial Support for Persons with Disabilities in Relation to the Covid 19 Outbreak in the Disability Center / Workshop for Disability Social Welfare Institutions (LKS), and Other Institutions. General Directorate of Social Rehabilitation (2020). Available online at: https://kemsos.go.id/uploads/topics/15852709524796.pdf (accessed March 7, 2021)

42. State of Qatar. Health and Safety Guidance for People With Disabilities. Ministry of Public Health (2020). Available online at: https://covid19.moph.gov.qa/EN/Documents/PDFs/safety_guide_disability_mar_07-eng.pdf (accessed December 9, 2020).

43. Government of France. People With disabilities. Government of France (2020). Available online at: https://www.gouvernement.fr/info-coronavirus/espace-handicap (accessed March 7, 2021).

44. Swedish Public Health Agency Government of Sweden. Information for Risk Groups About Covid-19. Swedish Public Health Agency (2020). Available online at: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/smittskydd-beredskap/utbrott/aktuella-utbrott/covid-19/skydda-dig-och-andra/rad-och-information-till-riskgrupper/ (accessed March 5, 2021).

45. Ministry of Health. Coronavirus, the New FAQ on Measures for People With Disabilities. Ministry of Health (2020). Available online at: http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/dettaglioNotizieNuovoCoronavirus.jsp?lingua=italiano&menu=notizie&p=dalministero&id=4328 (accessed March 7, 2021).

46. AGDSS. Coronavirus: Social Distancing - Easy Read. Australian Government Department of Social Services (2020). Available online at: https://www.dss.gov.au/disability-and-carers-covid-19-information-and-support-for-people-with-disability-and-carers/coronavirus-social-distancing-easy-read (accessed March 7, 2021).

47. Ministry of Health. COVID-19: Information for Disabled People and Their Family and Whanau. Ministry of Health (2020). Available online at: https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-information-specific-audiences/covid-19-information-disabled-people-and-their-family-and-whanau (accessed March 7, 2021).

48. Republic of South Africa. Sikhaba iCovid-19 Radio Series (15th July) Disability and COVID-19. (2020). Available online at: https://sacoronavirus.co.za//07/15/sikhaba-icovid-19-radio-series-1h-july-disability-and-covid-19/ (accessed March 2, 2021).

49. Australian Government Department of Health. Information for Support Workers and Carers on coronavirus (COVID-19) Testing for People With Disability. Australian Government Department of Health (2020). Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/information-for-support-workers-and-carers-on-coronavirus-covid-19-testing-for-people-with-disability (accessed March 7, 2021).

50. Department of Health Government of Puerto Rico. Recommendations for Application for a COVID−19 Home Laboratory Test for Populations With Special Needs. Department of Health Government of Puerto Rico (2020). Available online at: http://www.salud.gov.pr/pages/coronavirus.aspx(accessed March 7, 2021)

51. Government of France. Understanding the COVID-19. Government of France (2021). Available online at: https://www.gouvernement.fr/info-coronavirus/comprendre-le-covid-19 (accessed March 8, 2021).

52. NCDC. Scaling up COVID-19 Testing Capacity in Nigeria. Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (2020). Available online at: https://ncdc.gov.ng/reports/255/2020-april-week-15 (accessed March 8, 2021).

53. A Singapore Government Agency Website. Expanded Testing in Phase 2, Steady Progress in Dormitory Clearance. A Singapore Government Agency Website (2020). Available online at: https://www.gov.sg/article/expanded-testing-in-phase-2-steady-progress-in-dormitory-clearance (accessed March 8, 2021).

54. Government of Qatar. Information on Home Quarantine. Qatar: Information on Home Quarantine (2020). Available online at: https://www.moph.gov.qa/arabic/Pages/home-quarantine.aspx (accessed March 8, 2021).

55. Department of Health Welfare. Control of Coronavirus Infections in Home Services. Department of Health and Welfare (2020). Available online at: https://thl.fi/fi/web/infektiotaudit-ja-rokotukset/taudit-ja-torjunta/taudit-ja-taudinaiheuttajat-a-o/koronavirus-covid-19/koronavirustartuntojen-torjunta-kotiin-annettavissa-palveluissa (accessed March 8, 2021).

56. Australian Government Department of Health. Management and Operational Plan for People With Disability. Australian Health sector emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) (2020). Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/06/management-and-operational-plan-for-people-with-disability_0.pdf (accessed March 8, 2021).

57. CDNA. National Guidelines for the Prevention, Control and Public Health Management of COVID-19 Outbreaks in Residential Care Facilities in Australia Version 3.0. Communicable Diseases Network Australia (2020). Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/06/coronavirus-covid-19-guidelines-for-outbreaks-in-residential-care-facilities.pdf (accessed March 8, 2021).

58. Department of Health Welfare. Coronavirus and Disability Services. Department of Health and Welfare (2020). Available online at: https://thl.fi/fi/web/vammaispalvelujen-kasikirja/ajankohtaista/koronavirus-ja-vammaispalvelut (accessed March 8, 2021).

59. GOV UK. Travel Advice: Coronavirus (COVID-19). Government of United States (2021). Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/travel-advice-novel-coronavirus (accessed March 8, 2021).

60. Government of Peru. Coronavirus: Measures and Recommendations for Interprovincial Land Travel During the National Emergency. Government of Peru (2020). Available online at: https://www.gob.pe/8792-coronavirus-restricciones-recomendaciones-y-excepciones-para-el-traslado-de-personas (accessed March 8, 2021).

61. New New Exceptions for People With Disabilities and Their Families in the Framework of Social Preventive and Compulsory Isolation. Disability National Agency (2020). Available online at: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/noticias/nuevas-excepciones-para-las-personas-con-discapacidad-y-sus-familias-en-el-marco-del (accessed March 8, 2021).

62. Argentina Republic - National Executive Power. Recommendation Guide of the National Disability Agency for Households and Residences That House People With Disabilities in the Context of the Covid-19 Pandemic. Argentina: Disability National Agency (2020). Available online at: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/circular_if-2020-27591107-apn-deand.pdf (accessed March 8, 2021).

63. Regarding new coronavirus infections. Emergency Response Measures-2nd (Related to the Department of Health and Welfare for Persons with Disabilities). Available online at: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/000606418.pdf (accessed March 8, 2021).

65. Public Health Authority. Protect Yourself and Others From the Spread of Infection. Public Health Authority (2021). Available online at: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/smittskydd-beredskap/utbrott/aktuella-utbrott/covid-19/skydda-dig-och-andra/vad-galler-for-friska-sjuka-och-isolerade/ (accessed March 8, 2021).

66. Ministry of social development family. Recommendations for the Care of People With Disabilities in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Government of Chile (2020). Available online at: https://www.senadis.gob.cl/sala_prensa/d/noticias/8226/recomendaciones-para-la-atencion-de-personas-con-discapacidad-en-el-contexto-de-la-pandemia-por-covid-19 (accessed March 8, 2021).

67. NCDC. COVID-19 Resources. Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (2020). Available online at: https://covid19.ncdc.gov.ng/resource/ (accessed March 8, 2021).

68. Public Health Authority. Easy to Read Information on Covid-19. Public Health Authority (2021). Available online at: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/smittskydd-beredskap/utbrott/aktuella-utbrott/covid-19/informationsmaterial/lattlast/#lyssna (accessed March 8, 2021).

69. Government of Mexico. Practical and Accessible Recommendations to Take Care of Your Health and Your Rights in Times of Coronavirus. Me too (2020). Available online at: https://coronavirus.gob.mx/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Guia_para_personas_con_Discapacidad_Visual-Yo_Tambien.pdf (accessed March 7, 2021).

70. Government of Colombia. TIC Services for People With People With Visual and Hearing Disabilities. Government of Colombia (2020). Available online at: https://coronaviruscolombia.gov.co/Covid19/tic-personas-con-discapacidad.html (accessed March 8, 2021).

71. UNPRPD. Coronavirus Recommendations for Blind People. Alliance to promote the services of people with disabilities (2020). Available online at: https://inclusionydiscapacidad.uy/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/ONU_Recomendaciones_Coronavirus_Personas-ciegas_v3.pdf (accessed March 8, 2021).

72. State of Qatar. Preventive Measures for People With Disabilities Against the Coronavirus (Covid-19). Ministry of Public Health (2020). Available online at: https://covid19.moph.gov.qa/EN/Documents/PDFs/COVID-19%20Infosheet%20for%20People%20with%20Disabilities%20V4%5B1%5D-ENG.pdf (accessed March 8, 2021).

73. Government of South Africa. Safety Precautions Related to Basic Sighted Guide Skills Regarding the Covid-19 Virus. (2020). Available online at: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_documents/COVID-19%20Information%20for%20the%20visually%20impaired.pdf (accessed March 8, 2021).

74. CDC. People With Disabilities. Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (2021). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-disabilities.html (accessed March 7, 2021).

75. Ministry of social development family. How to Support Visually Impaired People in the Face of the Coronavirus Alert. Government of Chile (2020). Available online at: https://www.senadis.gob.cl/resources/upload/galeria/19c5079015fb51094b25796d72232d1e.png (accessed March 8, 2021).

76. Federal Ministry of Health of Germany. Sign Language. Federal Ministry of Health (2020). Available online at: https://www.zusammengegencorona.de/gebaerdensprache/

77. CDC. Public Service Announcements (PSAs). Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (2021). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/communication/public-service-announcements.htm (accessed March 7, 2021).

78. Public Health Authority. Easy to Read Information on Covid-19. Public Health Authority (2021). Available online at: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/smittskydd-beredskap/utbrott/aktuella-utbrott/covid-19/skydda-dig-och-andra/lattlast/#lyssna (accessed March 8, 2021).

79. Electronic government agency information knowledge society. Resources About COVID-19 in Accessible and Inclusive Formats. Government of Uruguay (2020). Available online at: https://www.gub.uy/agencia-gobierno-electronico-sociedad-informacion-conocimiento/comunicacion/noticias/recursos-sobre-covid-19-formatos-accesibles-inclusivos (accessed March 8, 2021).

80. National Council for the Development Inclusion of People with Disabilities -Visual. Accessible Information for the Visually Impaired. Government of Mexico (2020). Available online at: https://www.gob.mx/conadis/articulos/visual (accessed March 9, 2021).

81. Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment. Home Whats New. India: Department of empowerment of Persons with Disabilities (Divyangjan) (2020). Available online at: http://disabilityaffairs.gov.in/content/page/whats-new.php (accessed March 7, 2021).

82. Government of Mexico. Accessible Conferences. Government of Mexico (2020). Available online at: https://coronavirus.gob.mx/category/conferencias-accesibles/ (accessed March 9, 2021).

83. JFD. About the Consultation Table for the Hearing Impaired of the New Coronavirus. Japanese Federation of the Deaf (2020). Available online at: https://www.jfd.or.jp/2020/02/19/pid20272 (accessed March 9, 2021).

84. Communications regulation commission. Resolution 5960 of 2020 by Which Regulatory Measures Are Adopted to Guarantee the Deaf or Hard of Hearing Population Timely Continuous Communication Through Open Television, During the State of Economic, Social Ecological Emergency. Government of Colombia (2020). Available online at: http://www.insor.gov.co/home/descargar/Resolucion5960_CRC_LenguaDeSenas.pdf (accessed March 9, 2021).

85. The National Communications Entity Requests the TV Channels to Respect the Box With Sign Language Interpretation. Disability National Agency (2020. Available online at: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/noticias/el-ente-nacional-de-comunicaciones-solicita-los-canales-de-tv-respetar-el-recuadro-con (accessed March 8, 2021).

86. Government of Uruguay. Records for COVID-19 Are Formatted and Included. (2020). Available online at:https//www.gub.uy/sistema-nacional-emergencias/comunicacion/publicaciones/covid-19-atencion-discapacidad

87. Protect Yourself Others From Coronavirus Infections - Keep Going Every Day Responsibly. (2020). Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UI_OKY-QUZg&list=PLV8_D7-jawHTzCPheQ7y3HMVUoARQvW1a (accessed March 7, 2021).

88. Australian Government Department of Health. Auslan Version of Coronavirus (COVID-19) Accessible Resources. Australian Government Department of Health. (2020). Available online at: https://www.dss.gov.au/disability-and-carers-covid-19-information-and-support-for-people-with-disability-and-carers/auslan-version-of-coronavirus-covid-19-accessible-resources (accessed March 9, 2021).

89. United States. COVID-19 Frequently Asked Questions. (2020). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/faq.html

90. Mid East News. MOEHE Provides Distance Learning for Students with Disabilities. Mid East News (2020). Available online at: https://portal.http://www.gov.qa/wps/portal/media-center/news/news-details/moeheprovidesdistancelearningforstudentswithdisabilities (accessed March 9, 2021).

91. Government of Mexico. Guidelines for People With Hearing Disabilities. I Also. (2020). Available online at: https://coronavirus.gob.mx/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Guia_Para_Personas_Con_Discapacity_Audio-yo_Tambien.pdf (accessed March 2, 2021).

92. Centers for Disease Control Prevention. COVID-19 Videos. CDC (2021). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/communication/videos.html?Sort=Date%3A%3Adesc

93. Federal Ministry of Health of Germany. Sign Language. Federal Ministry of Health (2020). Available online at: https://www.zusammengegencorona.de/gebaerdensprache/ (accessed February 11, 2021).

94. Ministry of Health New Zealand Government. COVID-19: Information and Advice for the Deaf Community. MOH (2020). Available online at: https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-information-specific-audiences/covid-19-information-disabled-people-and-their-family-and-whanau/covid-19-information-and-advice-deaf-community (accessed March 9, 2021).

95. Ministry of Disabilities Government of Italy. COVID-19: Frequently Asked Questions About Measures for People With Disabilities. MOD (2021). Available online at: http://disabilita.governo.it/it/notizie/covid-19-domande-frequenti-sulle-misure-per-le-persone-con-disabilita/ (accessed March 2, 2021).

96. National Service for people with disabilities (SENADIS) Ministry of Social Development Family of Chile. SENADIS Launches Vi-sor Web Application to Assist Deaf People in Sign Language. SENADIS (2020). Available online at: https://www.senadis.gob.cl/sala_prensa/d/noticias/8195/senadis-lanza-aplicacion-vi-sor-web-para-la-atencion-de-personas-sordas-en-lengua-de-señas (accessed March 2, 2021).

97. National disability agency Government of Argentina. Video Call Service for Deaf People. NDA (2020). Available online at: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/noticias/servicio-de-videollamada-para-personas-sordas-e-hipoacusicas

98. National Service for people with disabilities (SENADIS) Ministry of Social Development Family of Chile. Civil Registry Has Masks Provided by Senadis for the Care of Deaf People. SENADIS (2020). Available online at: https://www.senadis.gob.cl/sala_prensa/d/noticias/8242/registro-civil-dispone-de-mascarillas-aportadas-por-senadis-para-atencion-de-personas-sordas (accessed March 8, 2021).

99. Government of Ethiopia. Coronavirus and Deafness in Ethiopia. Government of Ethiopia (2020). Available online at: https://am.al-ain.com/article/a-new-type-of-mask-designed-for-deaf-people-in-ethiopia (accessed March 8, 2021).

100. Government of United Kingdom. Government Delivers 250,000 Clear Face Masks to Support People With Hearing Loss. GOV UK (2020). Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/government-delivers-250000-clear-face-masks-to-support-people-with-hearing-loss (accessed March 8, 2021).

101. Government of Mexico. People With Disabilities. Mexico: government of Mexico; (2020). Available online at: https://coronavirus.gob.mx/informacion-accesible/#documentos (accessed March 7, 2021).

102. LNF. Application for Prevention and Assistance Measures for Persons With Disabilities in Lithuania. Forum of Lithuanian Disability Organizations (2020). Available online at: https://www.lnf.lt/kreipimasis-del-prevenciniu-ir-pagalbos-priemoniu-uztikrinimo-zmonems-su-negalia-lietuvoje/?lang=lt (accessed March 7, 2021).

103. Department of Rehabilitation Disability Government of Chile. Recommendations for Daily Cleaning and Disinfection of Technical Aids in the Context of COVID-19. Department of Rehabilitation and Disability (2020). Available online at: https://rehabilitacion.minsal.cl/recomendaciones-para-la-limpieza-y-desinfeccion-diaria-de-ayudas-tecnicas-en-el-contexto-del-covid-19/ (accessed March 2, 2021).

104. Ministry of Public Health Government of Qatar. COVID-19 Guidance for People Living With Heart Disease. MOPH (2020). Available online at: https://www.moph.gov.qa/Style%20Library/MOPH/Videos/guideheart.pdf (accessed March 2, 2021).

105. UN Partnership on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Government of Uruguay. Coronavirus Recommendations for People With Motor Disabilities. UNPRPD (2020). Available online at: https://inclusionydiscapacidad.uy/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/ONU_Recomendaciones_Coronavirus_Personas-discapacidad-motriz_v3.pdf (accessed March 8, 2021).

106. National Institute for Locomotor Disabilities Government of India. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Advice for the Public/PwDs. Divyangjan (2020). Available online at: http://niohkol.nic.in/Covid19.aspx (accessed March 8, 2021).

107. Government of Zambia. Wheelchair and Assistive Technology Users ATTENTION: PRECAUTIONS for COVID-19. (2020). Available online at: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_documents/Wheelchair%20AT%20COVID-19%20Precautions.pdf.pdf.pdf (accessed March 8, 2021).

108. Government of Mexico. Guidelines for People With Motor Disabilities. I Also. (2020). Available online at: https://coronavirus.gob.mx/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/guia_para_personas_con_discapacity_motriz-yo_tambien.pdf (accessed March 2, 2021).

109. National Institute for Locomotor Disabilities Government of India. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Advice for the Public/PwDs. Divyangjan (2020). Available online at: http://niohkol.nic.in/Covid19.aspx (accessed March 2, 2021).

110. Ministry of Health Government of Spain. Guidelines for People With Chronic Health Conditions and Older People in a Confined Situation. MOH (2020). Available online at: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov/documentos/CRONICOS20200403.pdf (accessed March 2, 2021).

111. Statement of the Japan Circulation Society Government of Japan. Prevention and Countermeasures of Cardiovascular Diseases in the Face of New Coronavirus Infections in Evacuation Centers. Statement of the Japan Circulation (2020). Available online at: https://www.j-circ.or.jp/cms/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/ (accessed March 2, 2021).

112. Ministry Ministry of Social Justice Empowerment Department Department of Social Justice Empowerment Government of India. Advisory for Senior Citizens during COVID-19. MSJE (2020). Available online at: https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s3850af92f8d9903e7a4e0559a98ecc857/uploads/2020/05/2020053135.pdf (accessed March 2, 2021)

113. Ministry of Health New Zealand Government. COVID-19: Advice for Higher Risk People. MOH (2020). Available online at: https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavir (accessed March 2, 2021).

114. Public Health England Government of United Kingdom. Guidance on Social Distancing for Everyone in the UK. PHE (2020). Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-guidance-on-social-distancing-and-for-vulnerable-people/guidance-on-social-distancing-for-everyone-in-the-uk-and-protecting-older-people-and-vulnerable-adults (accessed March 2, 2021).

115. Government of Canada. People Who Are at Risk of More Severe Disease or Outcomes From COVID-19. Government of Canada (2020). Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/people-high-risk-for-severe-illness-covid-19.html (accessed February 20, 2021).

116. Chauvin F; Higher Council of Public Health. Recommendations Related to the Prevention and Management of COVID-19. HSCP (2020). Available online at: https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/new_hcsp-sars-cov-2_patients_fragiles_v3-2.pdf (accessed February 20, 2021).

117. Institute of Hygiene Government of Lithuania. Number of People at Higher Risk of Developing the Serious Disease COVID-19 in Municipalities. HI (2020). Available online at: https://www.hi.lt/news/1610/1246/Didesnes-rizikos-susirgti-sunkia-COVID-19-ligos-koronaviruso-infekcijos-forma-asmenu-skaicius-savivaldybese.html (accessed February 20, 2021).

118. Department of Health Government of Puerto Rico. People With Asthma and COVID-19. DOH (2020). Available online at: http://www.salud.gov.pr/Pages/Personas_De_Mayor_Riesgo.aspx#asma (accessed February 20, 2021).

119. Swedish Public Health Agency Government of Sweden. Information for Risk Groups About Covid-19. Swedish Public Health Agency (2020). Available online at: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/smittskydd-beredskap/utbrott/aktuella-utbrott/covid-19/skydda-dig-och-andra/rad-och-information-till-riskgrupper/ (accessed February 20, 2021).

120. Zaman S, MacIsaac AI, Jennings GL, Schlaich M, Inglis SC, Arnold R et al. Cardiovascular disease and COVID-19: Australian/New Zealand consensus statement. Med J Aust. (2020) 213:182–7. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50714

121. Federal Ministry of Health Nigeria Center for Disease Control. Advisory for Vulnerable Groups (The Elderly and Those With Pre-existing Medical Conditions) Version 2, June, 2020. NCDC (2020). Available online at: https://covid19.ncdc.gov.ng/media/files/AdvisoryforVulnerableGroupsV2June2020.pdf (accessed February 20, 2021).

122. Ministry of Health Singapore. Advisory on Vulnerable Group. MOH (2020). Available online at: https://www.moh.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider5/advisories/advisory-on-vulnerable-group-(moh).pdf (accessed February 20, 2021).

123. Federal Ministry of Health of Germany. Older People and People With Previous Illnesses Should Especially Protect Themselves. Federal Ministry of Health (2020). Available online at: https://www.zusammengegencorona.de/informieren/aeltere-menschen/aeltere-menschen-sowie-menschen-mit-vorerkrankungen-muessen-sich-besonders/ (accessed February 20, 2021).

124. Centers for Disease Control Prevention. People With Moderate to Severe Asthma. CDC (2021). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/asthma.html (accessed February 20, 2021).

125. Government of Spain. Recommendations for People With Allergies and/or Asthma During the COVID-19 Epidemic. (2020). Available online at: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov/img/COVID19_alergia_asma.jpg (accessed February 20, 2021).

126. Government of Japan. Response to Bronchial Asthma Patients With New Coronavirus Infection. Government of Japan (2020). Available online at: https://www.jsaweb.jp/uploads/files/.pdf (accessed February 20, 2021).

127. Resolution MS. 1,541 / 20. Argentina. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Indications for Preventive Social Isolation. Risk Groups (2020). Available online at: http://news.ips.com.ar/files/rms154120.html (accessed February 20, 2021).

128. Ministry of Health Social Protection Government of Colombia. Guidelines for the Deployment of Actions for the Healthy Living Dimension and Non-Transmissible Conditions Including Orphan Diseases, During the Sars-Cov-2 (Covid-19) Pandemic. MOH (2020). Available online at: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/RID/gips14-orientaciones-ent-covid19.pdf (accessed February 20, 2021).

129. Government of Spain. Recommendations for People With Chronic Health Conditions. (2020). Available online at: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov/documentos/COVID19_Recomedaciones_cronicos_nueva_normalidad.pdf (accessed February 20, 2021).

130. Government of Spain. Recommendations for People With Cystic Fibrosis During the COVID-19 Epidemic. (2020). Available online at: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov/img/COVID19_Cartel_Fibrosis_Quistica.jpg (accessed February 20, 2021).

131. Minister Minister of Disabilities Presidency Presidency of the Council of Ministers Government of Italy. UILDM: COVID-19 and Neuromuscular Diseases Recommendations. UILDM (2020). Available online at: http://disabilita.governo.it/it/notizie/uildm-raccomandazioni-covid-19-e-malattie-neuromuscolari/ (accessed February 20, 2021).

132. Government of Singapore. Singapore's Re-opening (Phase 3) Online Resources for Caregivers. Government of Singapore (2020). Available online at: https://www.enablingguide.sg/resources/latest-information-on-coronavirus-disease-2019-(covid-19) (accessed February 20, 2021)

133. Developmental Disabilities Association Selkokeskus Finland. Reliable Information About the Coronavirus in Plain Language Supported by Images. Selkokeskus (2020). Available online at: https://selkokeskus.fi/selkokieli/materiaaleja/luotettavaa-tietoa-koronaviruksesta-selkokielella-ja-kuvin-tuettuna/ (accessed February 20, 2021).

134. UN Partnership on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Government of Uruguay. Coronavirus Recommendations for People With Autism Spectrum Disorder. UNPRPD (2020). Available online at: https://inclusionydiscapacidad.uy/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/ONU_Recomendaciones_Coronavirus_personas-con-TEA_v3-1.pdf

135. Government of Mexico. Guidelines for People With Autism. Me too (2020). Available online at: https://coronavirus.gob.mx/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Guia_Para_Personas_con_autismo-yo_tambien.pdf (accessed February 20, 2021).

136. Swedish Public Health Agency Government of Sweden. Easy to Read Information on Covid-19. Swedish Public Health Agency (2020). Available online at: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/smittskydd-beredskap/utbrott/aktuella-utbrott/covid-19/informationsmaterial/lattlast/#latt (accessed February 20, 2021).

137. Secretary of state in charge of disabled people Government of France. People With Disabilities, Caregivers and Professionals: Together Against COVID 19. Secretary of state in charge of disabled people (2020). Available online at: https://solidaires-handicaps.fr/informations/handicap/deficiences-intellectuelles (accessed February 20, 2021).

138. National National Institute for The Empowerment of Persons with Intellectual Disabilities (DIVYANGJAN) Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities (Divyangjan) Ministry of Social Justice Empowerment Government Government of India. Sensitizing People With Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities about Covid-19. Divyangjan (2020). Available online at: http://niepid.nic.in/Sensitizing_PWID.pdf (accessed February 20, 2021).

139. National Health Service Government of France. Supporting Patients of All Ages Who Are Unwell With Coronavirus (COVID-19) in Mental Health, Learning Disability, Autism, Dementia and Specialist Inpatient Facilities, Version 1. NHS (2020). Available online at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/04/C0290_Supporting-patients-who-are-unwell-with-COVID-19-in-MHLDA-settings.pdf (accessed February 20, 2021).

140. Ministry of Disabilities Government of Italy. COVID-19 and Autism: Indications From the ISS to Prevent Illness Linked to the Epidemic. MOD (2020). Available online at: http://disabilita.governo.it/it/notizie/covid-19-e-autismo-le-indicazioni-dell-iss-per-prevenire-il-disagio-legato-all-epidemia/ (accessed February 20, 2021).

141. Government of Mexico. Coronavirus: Mental Health. Government of Mexico. (2020). Available online at: https://coronavirus.gob.mx/salud-mental/ (accessed February 20, 2021).

142. Government of Spain (2020). Available at: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov/ciudadania.htm (accessed February 20, 2021).

143. Argentine Neurological Society. Release About COVID-19. Argentine Neurological Society (2020). Available online at: https://www.sna.org.ar/web/admin/art_doc/1157/RECOMENDACION_GRUPO_COGNITIVO_CORONAVIRUS_Y_ADULTOS_MAYORES.pdf (accessed March 11, 2021).

144. North Bay Regional Health Centre of Canada. Non-Pharmacological Approaches to Support Individuals Living with Dementia Maintain Isolation Precautions. North Bay Regional Health Centre (2020). Available online at: https://clri-ltc.ca/files/2020/04/BSO_COVID-19-Resource-Dementia-and-Maintaining-Isolation-Precautions-April-2020FINAL.pdf

145. Ministry of Public Health State of Qatar. A Daily Schedule While at Home for People With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Ministry of Public Health (2020). Available online at: https://www.moph.gov.qa/Style%20Library/MOPH/Videos/dailyscheduleASDen.pdf (accessed March 3, 2021).

146. Department of Health Australian Government. Fact Sheet: Information for Families. Supporting People With Intellectual or Developmental Disability to Access Health Care During the Covid-19 Pandemic. Department of Health (2020). Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/05/coronavirus-covid-19-information-for-families-information-for-families.pdf (accessed March 8, 2021).

147. Ministry of Health New Zealand Government. COVID-19: Supporting a Person With Dementia At Home. MOH (2020). Available online at: https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-information-specific-audiences/covid-19-supporting-person-dementia-home (accessed March 8, 2021).

148. Vaqué A; Rhône-Alpes Autism Resource Center. Guide for a Serene Deconfinement: for Adolescents Adults With ASD. CRAif. (2020). Available online at: https://gncra.fr/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/CRA-RA_Guide-d%c3%a9confinement-Adultes-Ados_VF.pdf

149. Ministry of Sports Government of Chile. Ministry of Sport Will Disseminate Physical Activity Routines Developed by Special Olympics. Ministry of Sports (2020). Available online at: https://www.mindep.cl/actividades/noticias/1579

150. Sichuan Jinkang Down Children's Rehabilitation Center. How Can Families With Mental Disabilities Do Well in Home Environment Protection Home Rehabilitation Training in an Epidemic Setting?. Sichuan Jinkang Down Children's Rehabilitation Center (2020). Available online at: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzA3Mjg2MzU0Ng = =&mid=2651225383&idx=1&sn=f03e72b6d20045f2959bbbbdf6a3bf61&scene=21#wechat_redirect (accessed March 8, 2021).

151. Department of Psychiatry National Institute of Mental Health Neurosciences of India. Mental Health in the Times of COVID-19 Pandemic Guidance for General Medical and Specialized Mental Health Care Settings. NIMHANS (2020). Available online at: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/COVID19Final2020ForOnline9July2020.pdf (accessed March 8, 2021).

152. Regional Regional Integrated Center for the Development of Skills Rehabilitation Rehabilitation Empowerment of the Disabled (CRC) Gorakjpur Department Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities (DIyangjan) Government Government of India. Sensory Activities for Children With Autism During COVID-19 Lockdown. CRC (2020). Available online at: https://niepmd.tn.nic.in/documents/sensory_autism_240420.pdf (accessed March 8, 2021).

153. National National Institute for Empowerment of Persons with Multiple Disabilities (Divyangjan) Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities (Divyangjan) Ministry of Social Justice Empowerment Government Government of India. Helping Child With Autism Get Good Sleep During Lockdown. Divyangjan (2020). Available online at: https://niepmd.tn.nic.in/documents/guidance_lockdown_030420.pdf (accessed March 8, 2021).

154. Ministry of Health of Republic Indonesia. Guidelines for Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in the Covid-19 Pandemic. MOH (2020). Available online at: https://www.kemkes.go.id/article/view/20043000003/pedoman-dukungan-kesehatan-jiwa-dan-psikososial-pada-pandemi-covid-19.html (accessed March 8, 2021).

155. National Service for people with disabilities (SENADIS) Ministry of Social Development Family of Chile. Protocol Will Allow Companions of People With Autistic Disorder to Travel in Total Quarantine. SENADIS (2020). Available online at: https://www.senadis.gob.cl/sala_prensa/d/noticias/8189/protocolo-permitira-que-acompanantes-de-personas-con-trastorno-autista-puedan-desplazarse-en-cuarentena-total (accessed March 8, 2021).

156. Saldarriaga Concha foundation. Bogotá Will Identify People With Disabilities. Saldarriaga Concha Foundation (2021). Available online at: https://www.saldarriagaconcha.org/ante-covid-19-bogota-busca-identificar-a-las-personas-con-discapacidad/ (accessed March 14, 2021).

157. SENADIS. Undersecretariat for Human Rights and SENADIS Receive Donation From Nestlé for People With Disabilities. Ministry of Social Development and Family (2020). Available online at: https://www.senadis.gob.cl/sala_prensa/d/noticias/8324 (accessed March 11, 2021).

158. AND. Recommendations and Care for People With Disabilities Due to Coronavirus. National Disability Agency (2020). Available online at: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/noticias/recomendaciones-y-cuidados-de-personas-con-discapacidad-con-motivo-de-coronavirus (accessed March 11, 2021).

159. Government of Brazil. Ministry of Citizenship Announces Measures for the Social Area and Guarantees the Offer of Assistance Programs. Gounvernment of Brazil (2020). Available online at: https://www.gov.br/cidadania/pt-br/noticias-e-conteudos/desenvolvimento-social/noticias-desenvolvimento-social/copy_of_ministerio-da-cidadania-anuncia-medidas-para-a-area-social-e-garante-a-oferta-de-programas-assistenciais https://handicap.gouv.fr/les-aides-et-les-prestations/prestations/article/prestation-de-compensation-du-handicap-pch (accessed March 14, 2021).

160. ACL Announces Nearly $1 Billion in CARES Act Grants to Support Older Adults and People With Disabilities in the Community During the COVID-19 Emergency. Administration for Community Living (2020). Available online at: https://acl.gov/news-and-events/announcements/acl-announces-nearly-1-billion-cares-act-grants-support-older-adults (accessed March 14, 2021).

161. Government of France. Compensation to Handicap. (2020). Available online at: https://handicap.gouv.fr/les-aides-et-les-prestations/prestations/article/prestation-de-compensation-du-handicap-pch (accessed March 8, 2021).

162. Ministry of Disabilities Government of Italy. COVID-19: Frequently Asked Questions about Measures for People with Disabilities. MOD (2021). Available online at: http://disabilita.governo.it/it/notizie/covid-19-domande-frequenti-sulle-misure-per-le-%20persone-con-disabilita/ (accessed March 8, 2021).

163. GOV UK. Get Support If You Are Clinically Extremely Vulnerable to Coronavirus. Government of United Kingdom; (2020). Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/coronavirus-shielding-support?fbclid=IwAR0ZciJdp3zC-6ZH8hDIWX2SO1_ijJWq4fexprK2e5Cr9fpbooEJLVON_mA (accessed February 15, 2021).

164. JFD. About the Consultation Table for the Hearing Impaired of the New Coronavirus. Japanese Federation of the Deaf (2020). Available online at: https://www.jfd.or.jp/2020/02/19/pid20272

165. Government of India. Different Capacities. Government of India (2020). Available online at: https://www.india.gov.in/people-groups/community/differently-abled?page=5 (accessed March 15, 2021).

166. Australian Government Department of Health. Information for Support Workers and Carers on Coronavirus (COVID-19) Testing for People With Disability. Australian Government Department of Health (2020). Available online at: https://www.dss.gov.au/disability-and-carers (accessed March 7, 2021).

167. Work Income The The Hiranga Tangata. Help With Living Expenses. Work and Income (2020). Available online at: https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-information-specific-audiences (accessed March 15, 2021).

168. UN. COVID-19 Emergency Appeal. (2020). Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/ZAMBIA_%20COVID-19_Emergency_Appeal.pdf (accessed March 15, 2021).